.jpg)

"...the victory of materialism in Russia resulted in the complete disappearence of all matter."

Andrei Biely

"How can[...]the religion that seeks the administration of justice in the world and man’s freedom from material and spiritual shackles, [be] the opium of the people?"

Imam Khomeini

A recent article by Michael Cuenco for Compact has, in analysing the legacy of Lenin and his haunting presence in contemporary politics, made the claim that a "21st Century Finland Station" event is an impossibility. Cuenco claims that "what separates today’s aspiring revolutionaries from the transformative possibilities of Lenin’s time is the fact that politics has since been emptied of much of its material and programmatic content; the terrain of ideological contestation has migrated from the field of political economy into the subjective realm of symbols, morals, and lifestyles, manifesting as an endless battle over the modes of personal expression." I take issue with this formulation of the problem, and with Cuenco's Janus-faced criticism of both contemporary revolutionaries and Lenin himself: first implying praise for Lenin's focus on "political economy", then a paragraph later applying the most austere denunciation of "Lenin and the murderous Bolsheviks" for their "Muscovite tyranny". With regard to his claim that revolution cannot occur because the self-styled revolutionaries are too caught up in a "subjective realm", repeating the tired Nu-Situationist critique of the Laschian post-Left, Cuenco accidentally stumbles into (and then immediately ignores) the real solution to his problem. Cuenco doesn't pause to consider why the conditions of our epoch and those of Lenin's may differ: rather than provide a historical analysis of the distinct political economic arrangement of our epoch to that of Lenin's, he simply bemoans the Left because they aren't doing it. The typical post-Left argument for why revolutionaries 'aren't what they used to be' is (at best) 'information overload', or (at worst) 'CIA IdPol'; I aim to follow a Leninist inquiry and propose that the reason a direct repetition of the Leninist moment is impossible is because its unnecessary. As Cuenco almost says but never quiet does, Lenin won, and we are living in the post-Leninist world. The world-historic challenges that Lenin faced were overcome and the world was built anew in his image - the present tasks are fundamentally new and different from those faced by Lenin, and to understand what our present tasks are we may look to the inheritors of his legacy, the Leninist Tradition as it manifests today, in both overt and covert forms; to repeat Lenin means to become something entirely novel, to become unprecedented.

Identifying the existence of a Leninist Tradition beyond self-styled Leninist communist parties means locating a tangible, identifiable connection either in theory or practise to the novel form of Partisan-Revolutionary practice initiated by Lenin and the Bolsheviks; above all, however, it means looking for 'the new'. Leninism's most famous and lasting formulation is that of the 'Party of a New Type', a novel form of organisation which doesn't delimit itself to the established parameters of legal parliamentary work or illegal insurgent activity alone, this concept of 'Party' is determined principally by dynamism, trajectory. For the sake of brevity I won't make this into another tired recapping of the history of the Leninist Party as it appeared in Russia - instead I'll try and provide a non-dogmatic, dynamic, open schema for what the 'Party of a New Type' is. If we take the Leninist notion of 'Party' seriously then to bracket the concept in immovable eternal categories would be unfaithful; our analysis is of the spirit, not the dead letter of the Leninist 'Party'. The Leninist conception of 'Party' is principally a Partisan body acting as a 'law unto itself', guided by an ambivalence to what Schmitt calls 'the bracketing of war': "By comparison with a war of absolute enmity [revolutionary war], the bracketed war of classical European international law, recognising accepted rules, is similar to a duel between cavaliers seeking satisfaction. To a communist like Lenin, inspired by absolute emnity, such a type of war must have appeared to be mere play, which he might join in if the situation demanded, but which basically he would find contemptible and ludicrous." (Carl Schmitt, Theory of the Partisan). Beyond this ambivalent attitude to bracketing the 'Party' is also unique in having an ambivalence to strict geographic boundaries: the task of the 'Party' is always universal.

Returning to Cuenco's issue with "symbols, morals, and lifestyles" apparently usurping the 'hard stuff' of political economy, a cursory look at the experience of internal discourse within the leaderships and inteligentsias of Socialist states shows clearly that struggles over "symbols, morals, and lifestyles" were principal concerns for the 'Actually Existing Socialisms' of the last century: questions concerning the function and production of art, for instance, were given significant attention; at the same time, the concept of the type of lifestyle and personality of the proper communist subject, the 'New Soviet Man', was intensely theorised and debated. Moreso than being a 'distraction from the economic question', the primary focus of politics turning to so-called 'subjective' concerns indicates something deeper about the nature of our present economy, reveals a fundamental correlation - if not a substantive unity - between our present economic arrangement and that of the former Soviet Union. Theorist Keti Chukhrov goes so far as to characterise the Dictatorship of the Proletariat as "an inner moral code" rather than as a continuation of class struggle in conditions of working-class political hegemony; the period of economic socialization therefore is the precondition to a modification of political discourse from 'hard' to 'soft', from 'objective' to 'subjective' concerns: "the aporia of struggle for more communism after successful revolution lies not in further resistance against capital; after the socialist revolution, the dictatorship of the proletariat and class struggle are aimed at preserving and equipping the already achieved condition of social classlessness. Which means in this case the very logic and method of anti-capitalist struggle is modified" (Practicing the Good: Desire and Boredom in Soviet Socialism).

With regard to the Leninist Tradition and the 'Party' this supposed 'subjective' turn ought to be understood aesthetically; in his Aesthetic Lectures Hegel's concept of the theefold aesthetic movement of Spirit, from Art to Religion to Philosophy, provides a historical schema by which we can assess the determinations and genealogies of contemporary political-aesthetic projects. Art as principal determination (Hegel's understanding of Greek civilisation) becomes the ideological object of certain contemporary theorists & political activists, notably principal theorist of the Post-Left / New Right Camille Paglia. Paglia's interest in Christianity is primarily in what she discerns to be its 'essence' in a chthonic paganism, a dark vitality animating the inert symbolic matter of Christianity; this we can call an 'artistic' orientation, a 'nothing new under the sun' orientation whereby religion, philosophy, and politics are a mere set of masks worn by the 'artistic', typically formulated as 'eros', 'erotics'. This retreat into the 'artistic', denying the qualitative transformation from art into religion in the movement of Knowledge, is characteristic of a politics of the body, of physical determination - despite appeals to the 'spirit' in New Right political discourse, typically the 'spirit' is understood only in its physical-bodily manifestation, in fitness, prettiness - the decorative body, that which is pleasing to the eye, is a good, is synonymous with virtue. The historical movement from the artistic to the religious orientation of course doesn't abolish Art, as philosophy in turn doesn't abolish religion; both are regrounded in the movement of Spirit to its more adequate articulation, in and through Art objects as the means of interfacing with Spirit in its movement toward 'full disclosure'. With this 'artism' an analagous-but-antagonistic 'religious' retreat, styled as 'revival' or 'return', is readily identifiable in contemporay political-philosophical aesthetics, most apparent in the 'post-liberalism' of Milbank, Pabst, Glasman, et al. Distinct from determination by eros and the body, the contemporary retreat into religion roots itself in notions of 'covenant' or 'compact', the reasonable settling of antagonisms in a revived 'commons' with a strong emphasis on the mediative power of legacy religious institutions. Other forms of the religious retreat take on a 'mystical' orientation superficially opposed to post-liberalism, a non-praxis of asceticism, inaction, hermitism in diametric opposition to the Bacchic erotics of the New Right and post-liberalism's institutionalism.

Post-liberalism's 'religion', the 'mysticism' of the nu-ascetics are both, with the New Right's 'art', a retreat into fantasy (a fantasy which nonetheless opines for and expresses itself as non-fantasy, as objective, concrete, against simulation and simulacrum), the construction of an elaborate and internally-coherant political metaphysics providing moral-asethetic respite to adherants' unhappy consciousness: these retreats are motivated by intense grief at 'decline', incapable of negotiating with and finding the exhilaration of present experience, to 'reveal' the joy masquerading as malaise. Grief, motivating the New Right, the 'mystics', and post-liberal poilitics, reveals a fundamental qualitative unity, the eschewing of an enjoyment of 'decline'; In not reckoning or recognising their joy they erect and attempt to satisfy themselves with dead forms, ideological-theological fetish objects. The task of an adequate politics therefore is the unleashing of joy; against retreat, against the resurrection of the old, a politics of joy, exhilaration, and genuine novelty. Novelty is not to be found in either tired Dionysianism, or stringent structural-Catholicisms, nor the purgative silence of mysticism; to unleash the new we must look to the organisation of the new, to build a 'Party of a New Type'. This 'Party', as with the politics of retreat outlined above, must be an organisation premised in what Cuenco derisively refers to as the "subjective realm". Lifestyle is not a secondary matter to political economy today, not in the age of information-attention economy wherein the strict MCM' circuit of 19th Century Capitalism finds itself subordinated to abstract socially-determined circuits, wherein capital and the state find themselves so inexorably intertwined as to arrive at the formation of a non-capitalist civic-managerial class, one (increasingly) directly antagonistic to the interests of capital and labour alike. Unfortunately for Cuenco, "symbols, morals, and lifestyles" comprise the raw material of contemporary political economy, and his desire for a return to the 'real' economic and programmatic politics of the early 20th Century represents yet another politics of retreat, an ignorance to the objective circumstances of the present condition - ironically, a retreat into the pre-Leninist era. So, against these political-aesthetic deserters and fantacists, how might our 'Party of a New Type' look?

Essential to the politics of retreat is a (covert) certainty of their own failure to achieve anything, the enjoyment of a lost cause. One unifying and determining feature of these orientations is the logic of exponentially compounding grief, positive feedback ever-intensifying into a malaise that renders all political activity utterly hopeless: 'Nothing Ever Happens'. When the cause is lost it is 'pretty', whereas revolutions are always 'ugly'. But the 'Party' can't be just the realisation of a negatively-determined 'politics of advancement' against the retreat - it must be the satisfaction of the desires expressed by the unhappy consciousness of its enemy. The task of the 'Party' is to uncover the fundamental unity of joy and grief, to 'convert' or reveal the grief as joy: "pleasure can shift into disgust or into a strange feeling of distance. The key point is that, in this violent upheaval, nothing changed in reality: what caused the shift was merely the change in the other's position with regard to our phantasmatic frame" (Zizek, The Plague of Fantasies). Perhaps in order to understand the objectives of this politics it's necessary to look to somewhere outside the so-called 'declining' West, somewhere where these psychic hang-ups don't dominate. Look East: a political aesthetics is rising, one dwelling within that same determinant "subjective realm" as our native politics, which embodies the 'artistic' and the 'religious' while overcoming (rather, side-stepping) the Western trap whereby grief becomes the singular totalising transcendental structure of political thought. This aesthetic locates itself in a wholly novel iteration of Partisan activity: Lebanon's Hezb'Allah, the Party of God.

Before discussing Hezb'Allah directly it's necessary to outline its genealogy. In August of 1920 the Executive Committee of the Third International held the Congress of the Peoples of the East in Baku, Azerbaijan. At this gathering Zinoviev, Chairman of the proceedings, declared outright that the common task of the communists and the peoples of colonised asia was Jihad against Western (in particular British) capital: "Arise, peoples of the East! The Third International summons you to a Holy War against the carrion-crows of capitalism..., propagate the idea of a federation of oppressed nations... create a union of the proletarians and peasants of all countries, religions and languages." The language of the Baku Congress seamlessly slid between Qur'anic exegesis and Leninist agitation; condemnations of clerical hypocrisy and landlordism uttered without reservation or caveat, "Even according to the shariat, the land can belong only to him who tills it, and not to the clergy who have grabbed it, like the mujtahids in Persia, who were the first to violate the fundamental law of the Moslem religion... This mask of sanctity must be torn from them, comrades, and the land they own must likewise be wrested from them and given to the working peasantry. [Applause.]".

It could be said that that Baku's vitalistic divine exhilaration, this preaching of Soviet Leninism in the language of a proto-Islamism, reveals a shallow and vain attempt to command and redirect the passions of Asian Muslims into fulfilling Russian geopolitical interests, a cynicism akin to the CIA & NATO's weaponisation of Catholicism in Italy during the Years of Lead or Poland during the Lenin Dockyards strike. It is entirely irrelevant as to whether the intention of the Soviets at Baku were honest or not: the seamlessness of Zinoviev's weaving of Marxist theory and Islamic thought, and the overwhelmingly popular reception to the Third International's position makes accusations of a cynical capture of the Islamic imaginary appear hollow. Instead it proves to be in reality an unleashing of the possibilities of an Islamic politics - an Islamic politics which would eventually turn its guns on the legal inheritors of the Congress organisers, against Brezhnev's Soviet Union in 1978. Hostilities against the Communist government in Afghanistan escalated to war in '79, the same year Ayatollah Khomeini assumed control of Iran, world-historic events consolidating the contemporary 'Islamic World', coinciding with the assumption of Margaret Thatcher to power in Britain and Deng Xiaoping in China.

The breakdown of Soviet communism is directly proportional to the rise of political Islam, that much is evident. In 1985, while the Communist world was rocked by endemic crises of economy and identity, Hezb'Allah released its Open Lettter Addressed to the Downtrodden in Lebanon and the World, a short manifesto outlining the Party's aims and principals. The text echoes much of the same sentiment expressed by Zinoviev at Baku, proclaiming the task of their Party first and foremost as universal, assuming the mantle of vanguard of the oppressed of all nations: "what befalls the Muslims in Afghanistan, Iraq, the Philippenes or elsewhere befalls the body of our Islamic nation of which we are an indivisible part... As for our friends, they are all the world's downtrodden peoples". The Open Letter invokes directly the same rousing, empowering, universalist language pioneered by the Bolsheviks and interwoven with religious-apocalyptic drama by communists at Baku: "O partisans and organized people, wherever you are in Lebanon and whatever your ideas, we agree with you on major and important goals embodied in the need to topple the American domination of the country, to expel the Zionist occupation that bears down heavily on the people's lives... Come, let us rise above quarrelling over minor issues and let us open wide the doors of competition for achieving the major goals". This invitation to revolutionary discourse, the opening-up of a grand experimental contestation of ideas, bears a striking similarity to Mao's famous "hundred flowers" declaration. The Open Letter ends with another equally post-Maoist invocation: "It is not important that a certain party control the street. What is important is that the masses interact with this party".

Hezb'Allah since '85 has become the principal regional antagonist in the conflict between the Islamic and Western worlds, a primary consequence being the rapid acceleration of Israel's military development and a runaway arms race between the IDF and Hezb'Allah. A significant aspect of this, owing to Hezb'Allah's dynamic approach to military and political strategy, is the attempt by certain elements within the IDF to counter their enemy's dynamism with a faster-moving, more experimental approach to military theory to 'out-nomad' the nomadic war-machine. The Operational Theory Research Institute (OTRI), led by Brigadier General Shimon Naveh, worked to reground Israeli military strategy in a theoretical model called 'Systemic Operational Design' (SOD). SOD functioned as an anti-doctrine, drawing from (most famously) Deleuze & Guattari, as well as other atypical theoretical sources to become strategically impervious to the typically more dynamic forces of Islamic resistance. OTRI was eventually sidelined, scapegoated for the failure of the 2006 July War - I only mention OTRI and SOD to demonstrate how certain elements within Israel's defence-intellectual circles conceive of the conflict with Hezb'Allah and where they turn theoretically to counter them is telling. One anecdote from a soldier who served under Naveh demonstrates the purpose of SOD: "We interpreted the alley as a place forbidden to walk through and the door as a place forbidden to pass through, and the window as a place forbidden to look through, because a weapon awaits us in the alley, and a booby trap awaits us behind the doors. This is because the enemy interprets space in a traditional, classical manner, and I do not want to obey this interpretation and fall into his traps. […] I want to surprise him! This is the essence of war. I need to win […] This is why that we opted for the methodology of moving through walls." To move through walls, to circumvent established engagement with space and motion - this is how the state attempts to match up to the man of war - turning to 'Deleuzian military strategy' is a compliment to the enemy, and its erasure from IDF doctrine is unsurprising: "From the standpoint of the State, the originality of the man of war, his eccentricity, necessarily appears in a negative form: stupidity, deformity, madness, illegitimacy, usurpation, sin." (Deleuze & Guattari).

The IDF's brief foray into non-standard 'postmodern' military theory begs the question of what officers like Naveh saw in their enemy that necessitated this irregular pivot in defence doctrine. A term used by Haz (InfraRed) to describe the Hezb'Allah phenomenon is as an 'Angelic Materialism', an overcoming of the perceived gulf between the cold materiality of warfare and the depths of religious traditionalism: "When Napoleon’s armies were fighting Austria Napoleon represented the raw materialism and rationalism of war: no sentiments, no religion, just raw material war… but the crazy thing about Hezb'Allah is that, for the first time, they combined religious traditionalism with the effectiveness of modern combat… they are materialist in in the sense that they’re submitting to the laws of warfare, while also submitting to the laws of God." Angelic Materialism as a foil to Naveh's 'Rhizomatic Zionism' echoes the attempts of certain continental thinkers operating within and adjacent to Marxism to redress and overcome tendencies endemic to 'left-wing' intellectualism since the '60s - against the inhumanisms, posthumanisms, antihumanisms: humanism, the struggle for universal humanity. With these tendencies of post-, anti-, etc. we find a side-stepping of the problem of alienation, or in some cases (namely Deleuze & Guattari) an affirmation of alienating forces as the singular wellspring of creativity and innovation, premise of the Accelerationist maxim "the only way out is through". Autonomist Marxist Mario Tronti had in his later years decoupled entirely from the developments which succeeded him, the 1970s Post-Operaismo and continental academic leftisms which had run parallel to his own work were now cast off entirely in favour of a project which aimed for a reappraisal of the pre-modern universalism prior to (and precondition for) Communism, Christianity. Tronti's later works weave the language of apocalypse and Messianism quarrelling into the classical European Marxist register, a thoroughly Western and contemplative version of the fiery Eastern didacticisms of Zinoviev at Baku, or the Hezb'Allah Open Letter. Tronti:

What is the workers’ movement missing? There were Desert Fathers. They were not listened to. But this is not their task, to be listened to in their own time. No, it is rather the seed cast into the field of the future. But in order that the plant comes forth, grows, bears fruit, and that the fruit not be lost, something else is needed. What is the message missing? I know it’s scandalous to even think it: what is missing is the Church form. That, it must be said, was attempted but did not succeed. The Revolution requires the Institution: to last not decades but centuries. This is the Church. To be conserved in time, for those to come, the liberatory event, always a momentary act – the taking of the Winter Palace – must be given a form. The transmutation of force into form is politics that persists, and then – only then – does it become history, comprehensive, complete and undiminished. And it is necessary to know, woe betide those who do not know it, that history, before the institution that contains it, is a permixta of good and bad... As Hegel said before Marx, whosoever wants die Weltändern, to transform life, must first of all come to terms with that ineliminable and irresolvable mysterium iniquitatis of the human condition and, with peace in their heart, struggle without hope of a definitive revelatio at the end of days.

The shift from cold, hard 'objectivity' into the hotter register of Messianism and religiosity is not as straightforward as a subjective cosmetic wrapper for materialism, but the blossoming of dialectical materialism into a mature orientation - the 'mystical' kernel uncovered from the 'rational' shell. Tronti's assertion of the necessary movement from Party-form to Church-form is not an attempt to put dialectical materialism upside-down again, but to firmly plant its feet where before they was hovering. Tronti's mission here was to pull Communism down from the clouds of detached formal rationalism and to recognise its concrete associations and continuity in the mud and muck of historical spirituality - from the perspective of Marxism-Leninism, wherein almost every socialist state conceived of itself, at one time or another, as in continuity with or satisfaction of prior mystical/religious stirrings (the proletarian hagiographies of Jan Hus and Thomas Muntzer, contemporary Chinese reappraisals of the Taiping Rebellion, Democratic Kampuchea's assertion of a geosophic Angkor revanche, etc.), Tronti's conception of real movement as a redemptive historical process is entirely continuous with the emergent self-concepts in the historical index of Actually Existing Socialism(s). Turning to more practical concerns: commodity fetishism, the mechanism by which de-alienation is phantasmatically promised and given to the Capitalist subject in incomplete and insufficient parcels is redeemed, brought to totality, by the secret name of this desire animating commodity production and exchange. Communism as the transmutation of force into form, the realisation of partial event or suspended logic into lasting and irrevocable transformation: in Revelation the destruction of Babylon the Great is immediately followed by the marriage of the lamb (Rev. 19:6-10), indicating a transformation in the substance of the City - Babylon is clothed in gold and jewellery like Jeruselam, only Jeruselam is entirely transparent, removed of the veil of sin. Approaching Revelation not metaphorically but as ontological allegory we read an explication of substantial reorganisation/transformation, one which is participatory.

"The [redemption] can be performed by man only, for he alone is made in the divine image and comprises the higher and lower orders" (Sheney Luhoth ha-Berith). Contrary to typical conceptions of mashiach, certain Kabbalists influenced by the 16th Century Safed School consider messianic redemption as the culmination of redemptive activity of the people at large unfolding in time, officiated by the Messiah as a kind of signature on the work of the people. This transformation of Messiah from standard-bearer of utopia to officiator of the acitivites of the masses repositions Judaism’s yearning for redemption into practical work, rising from the level of abstraction to that of the concrete, and in so doing folds both the anthropogenic exile and the future redemption into a phenomenal, material procedure. The Messiah-as-signatory brings us back to Hezb'Allah - not necessarily the Islamic organisations in Lebanon and elsewhere, but the name and conceptual significance of a 'Party of God' that have been opened up by the Hezb'Allah group(s). If approached from a Kabbalistic vantage the concept 'Party of God', being a collectivity acting as instrument of God's will, is (in essence) of God: "His will and wisdom are one with His very essence and Being, in a complete unity, and therefore it is as if He is given us He Himself!" (Tanya, Chapter 47). For God to be one with his will and wisdom means the Party of God can be considered a vehicle of incarnation, the articulation of God's will being metaphysically identical to God Himself. With the concept 'Party of God' conceived in this way we may override the inactivistic concept of Messiah as separate autonomous 'subject' acting independently from (while guiding and shaping) the physical World, a mirror to Hegel's Demiurgic conception of Idea. We can instead, building upon the post-Lurianic conception of Messiah as signatory of the collective work of the masses, conceive of an outline for the consolidation of an organised and directed redemptive army, rising from the twin abstractions of dogmatic religion and doctrinaire atheistic-rationalism to the concrete regime of Angelic Materiality.

Returning briefly to the enemy of our conceptual 'Party of God'—the operative logic of the politics of retreat being grief and resentment, we may look to and learn from those for whom the Spenglerian 'decline' hasn't penetrated or even surfaced in their political aesthetics. Hezb'Allah, as international outgrowth and extension of the Islamic Revolution which began in Iran '79 (and which I claim traces back to Baku '20), banishes the western trap of reciprocal compounding grief by means of martyrdom. From the lowest to highest orders of Hezb'Allah's aesthetic logic martyrdom dominates; the ultimate anunciation of exit on the level of the individual political soldier leading into the geopolitical, transnational level, and ultimately to the Messianic and apocalyptic level (for which there is no seperation or contradition - all action rendered/revealed in/as martyrdom smooths-out striations and degrees). Rather than vocalising resentment to the present condition, voice which leads to retreat, the martyr speaks in and through the fatal strategy of self-annihilation. Vince Garton writes in Language Inhuman: "There are two ways in which the endless speech of the liberal philosopher, or sophist, may come to an end. One is death... It is the shadow of death, the willingness to stake one’s life, that secures the mutual recognition that is a prerequisite of any freedom worth the name." The western political logic typically follows the schema of 'voice', into 'action', with the aim of some substantial transformation as the result. This schema is born out in the preponderance of manifestos, petitions, legal battles, letter writing campaigns, "have your voice heard" (even terroristic acts exist in tandmen with and for their anunciation in news media); ultimately political action begins and ends at the level of voice, with action as an intermediary phase dominated by vocalisation. Vince summises this domination by language as the essential premise of liberalism: "Tentatively, we may identify [liberalism] as the supremacy of language. The property rights that liberalism promotes are the inscription of social relations in the crystal language of law.". The capture of action by language returns us to Cuenco's article and this idea of the 'subjective realm' that exists supposedly at odds with objectivity and materiality. Vince offers a pointed articulation of this simulacrum Cuenco desires to overcome:

"The other means by which the liberal speech-flow may be ended is by its perfect completion. In this case, the network of symbols would become self-sufficient. Rather than meaninglessness and decoherence, however, the simulation would attain self-referential significance. This is the posthistorical possibility that Hegel saw prefigured—yet recoiled from—in the Confucian universe of signs. Instead of asserting different viewpoints according to the formal transformations of a single linear method, it would already be capable truly of expressing anything, and as such would be impossible to contradict... Because it is unparadoxical, because it cannot encompass death, the liberal regime cannot ever fully recuperate every possible contradiction—though it is more successful in doing so than any other system before it. Simulation must instead be pushed further. To establish the identity of A not just with A but with not-A through the medium of time constitutes the decisive move from synthetic parathesis to authentic synthesis. Formal contradiction then becomes impossible. ‘Debate’, in any particularly meaningful sense, comes to an end because everything has already been said. Such a circumstance becomes possible only through the completion of the process of simulation."

To pursue a politics of advancement into the 'subjective realm', wherein "the liberal speech-flow may be ended", will require Western political actors to shed their fear of the 'unreal' and the 'simulated', to halt their pursuit of 'reality' and instead pursue that which the martyr doesn't shirk from. The contemporary Occidental conception of reality must be revealed as contingent, held together by mystifying brackets and premised on a dismissal of spirit which renders western subjects incapable of recognising their own muddled spiritualities; ultimately losing sight of their own being in its historical becoming. The martyr isn't merely operating on the level of a willingness to self-sacrifice, but also has embraced outright the Eschatological task of overcoming subject/object and the ceaseless discursive loops of western sophistry which maintains that metaphysical gulf. Martyrdom in this formulation breaks the transcendental frame of grief and resentment. By the martyr throwing himself directly into simulation, action and anunciation are inseperably conjoined, apparent contradictions between faith/tradition and technological development are dissolved entirely. Material is rendered Angelic therefore by the synthesis of life and death in the outlook of the martyr (martyrdom as political orientation: at once personal, civic, and civilisational), in the dismissal of the dichotomy 'reality'/'unreality' for a commitment to wisdom, by a transvaluation of political-economic values: positing simulacrum's base reality against orthodox conceptions of base/superstructure which in their day helped demystify economy, but now more often than not are crudely employed to erect an internally coherant metaphysics, a dead letter fantasy-materialism (I oppose fantasy to simulacrum in so far as we can understand fantasy as a parcel cut out from totality, and simulacrum as an unavoidable and general feature). Angelic Materialism strives to ground itself in the historic unfolding of simulacrum: disolving arbitrary striation, dichotomy, opposition and degree with the aim of unearthing and exploiting/overcoming fundamental oppositions and antagonisms, approaching history as a univocal entirety wherein the 'subjective' is inexorable from 'objectivity'. This means apporaching faith not from the vantage of detached structural analysis (the approach shared by postliberals, New Rightists, and vulgar atheists), but as integral and essential to humanity's historical becoming; faith must be studied with passion and immersion—the Party of God would be such an entity that respects legacy religious institutions only insofar as they themselves match up to this task of passionate inquiry.

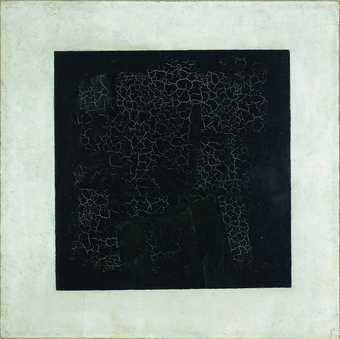

Here I want to turn again to the postliberals in particular as the enemy of our Party of God. Whereas the New Right tends towards honesty in its 'erotic paganism' and its simple formula 'pretty=good', the postliberals obscure themselves in veils of 'rooted' religious metaphysics. Postliberals like John Milbank will cite the heavy-hitters of Western Christianity to bring us such novel insights as "Beauty is, as Aquinas says, 'what pleases the sight'" (!)—Milbank's conception of the Beautiful (from Theological Perspectives on God and Beauty; Beauty and the Soul), while being metaphysically sophisticated and relatively novel, is still mired in the standard aesthetic logic I laid out above, melancholically charged by the compounding circuit of grief-resentment: "In the High Middle Ages, the possibility and experience of seeing the invisible as invisible... was generally assumed and pervaded life, art and understanding. Therefore, there was no specific discipline of "aesthetics," which arose in the eighteenth century. Beauty took care of herself." Milbank refers to a Kantian "modern cult of the sublime", a sinister conceptual antagonist leading man to "hypostastize and consecrate the unknowness as the force of nullity", which annihilates the possibility of Beauty outright: "In modernity... there is no mediation of the invisible in the visible, and no aura of invisibility hovering around the visible. In consequence there is no beauty." Milbank here corresponds somewhat with Kandinsky in his treatment of Malevich's Black Square, the singular 'point' without motion or line being the bare evocation of death; whereas Kandinsky is committed to the revival of the Beautiful in and through the spirituality of concrete abstraction, Milbank suggests a total void in modernity in its entirety, denies the possibility of the spiritual as Kandinsky conceives it. Of course the typical markers of the postliberal orientation are all present in Milbank's treatment—the essay is enitrely (internally) metaphysically coherent, self-satisfied; despite a condemnation of "mere prettiness", for instance, Milbank still maintains the possibility of a "prettiness that is a true species of beauty", collapsing back on an identification of formal cosmetic attractiveness with the Beautiful. Milbank's argument can be summed up as an attempt to refute what he regards as the Kantian error of falsely cleaving Sublimity and Beauty apart, rendering Beauty wholly subjective: "Modern beauty after Kant is therefore a 'raped' beauty. She appears only in that scene where she is violently surrounded and delineated, and desire for her arises not from her instigation, consent and production, but is wrenched from her as an entire appropriation of all her form to the (dis)interest of our feeling". Notwithstanding scandalising and moralising language, this anthropomorphic transformation of Beauty into a kind of animate Demiurgos acting and impressing upon man (an example of postliberalism's demand for re-enchantment) 'divinises' Beauty. This conception of Beauty then derives from a wholly opposite and (in my view) insufficient interpretation of spiritual incarnation to the one I laid out above, being the participatory historical work of the people revealing-incarnating Godliness in and through themsleves (Tronti: "In the Magnificat we read: bring down the powerful, raise up the humble. This is theology. How to bring down the powerful, how to raise up the humble? This is politics").

By the divinisation of Beauty I mean fetishisation, per Kojève: "Man will see that the absolute essential-Reality is also his own. As a result, it will cease to be opposed to him; it will cease to be divine"—this cessation of divinity (or, disenchantment) is adjacent to Tronti's project, the dragging back to earth of a detached Marxism and its re-envelopment into historical real movement. What I'm concerned with regarding Milbank is not necessarily a philosophical conflict around the definitions of Sublimity and Beauty, nor a defence of Kantian aesthetics. The issue I take is with aspects of his conception of the Beautiful disclosed by his poetical overinvestment of value into the Beautiful as something over and above humanity. What Milbank does (the rest of his essay being an affirmation of religious metaphysics concerning reciprocity with God) is reaffirm a radical distance between God and humanity, and the necessity for a certain form of mediation; ultimately what Milbank offers is an implicit metaphysical justification for his commitment to the mediative legitimacy of legacy Church institutions. Returning to Milbank's unfortunate rape metaphor: the Beautiful in Milbank's conception as a force acting relationally-but-opposed to humanity, a Divine Beauty, Kojève forwards in his treastise on non-representational painting a conception of the Beautiful that Milbank would likely consider criminal, a conception of the Beautiful which is incarnated in an extraction: "Art is the art of "extracting" the Beautiful". Kojève develops his argument specifically in the context of Kandinsky to say that 'prettiness', like that of representational/figurative painting, is deficient in that it is merely relying on the pre-existing 'object' then 'subjectively' re-presented on the picture plane—Kandinsky however brings painting to objectivity: "the circle-triangle is in its totality; it exists then without me, just as does [a] real tree. And if the circle-triangle is born, it is born like the tree is born from the seed; it is born without me; it is an objective birth; it is the birth of an object." Here we arrive at an outline for the 'theological' orientation of our Party of God: Our 'God' is not reliant on humanity, exists in-by-and-for-itself; He is an objective God, concrete and autonomous God—"Is it necessary to say the universe is "subjective", that it is the result of a "subjective" act, if one admits that it was created by God? Of course not. It is the same with the "total" tableau... [the non-representational painting] is just as independent of [the painter], just as objective—in its origin and in its being—as a son is objective and independent of his father". The Beautiful is, in this orientation, created ex nihilo by human work, does not independently 'act' as an Archon but is incarnated as independent, concrete, self-reliant. On another point, where I disagree with Kandinsky (and no doubt Milbank) regards Malevich's Black Square: in Black Square we have an objective incarnation of oblivion, of non-being, existing in-by-and-for-itself, a painting intended to end painting outright; and yet, this work was not the final 'full stop' that Kandinsky reads in it, but the zero-point of another beginning in painting, the incarnation of the new, the abgrund upon which Spirit could begin flight again unbracketed by prior formal constraints. Kandinsky's error is one of time and place, inability to anticipate the historical consequence of this 'lone point'. To understand Black Square as incarnate non-being we might consider the Kabbalistic ein-sof, boundless void which contracts within itself to cleave out a 'space' for the blossoming of materiality. Its neither a coincidence nor a cheap joke that Malevich hangs his Black Square diagonally against two walls in the corner of the space for 0,10: The Last Futurist Exhibition, a traditional place for the hanging of Icons. In the Orthodox continuity Icons are literal incarnations; Malevich here is paying proper reverence for his incarnation of the boundless nothing from which creation arises. In summation, with regard to the Party of God, the 'God' of the Party is Malevich's Black Square; incarnate non-being.

"He will know [essential-Reality] not in a Theology, but through an Anthropology. And this same Anthropology will also reveal to him his own essential-Reality: it will replace not only Religion, but also Philosophy" (Introduction to the Reading of Hegel). But to truly 'replace' religion and philosophy requires the adequate inheritance of both. Stalin said "the religious feelings of the masses must not be offended", but we should go further: 'religious feelings' must not be simply respected from a cold discrete distance, they must be lived, recognised and embodied outright as aspect of the totality of universal humanity. To reject anything you ought to first recognise it as a property of totality and therefore critique a thing not by banishing or abolishing, but by revealing it as simply insufficient, and drawing from it the maximal potential for advancing the march of Spirit.